Beverly Cleary, Red Rain Boots & Messy Adventures

Or why I ask about wonder and when you knew you'd be at home in the world.

Beverly Clearly died this week.

When the news alert popped up on my phone, my first thought was of red rain boots. Then, perhaps simultaneously, of wonder and mischief.

Can you imagine leaving behind a legacy like that?

It wasn’t just that I loved Ramona Quimby (though I did), rather, it was Cleary’s recognition — her delight and her approval — of young girls (like me) filled with what sometimes felt like too much of that wonder and mischief. She knew just what to do with girls like that… give them obstacles, let them stumble around and say too much or too little, let them antagonize and then feel sorry for themselves. Let them desire — really openly desire — things that served no purpose beyond bringing them joy.

Before Anne Shirley and Jo March, Ramona arrived right on time. At that age, we don’t know — but are starting to suspect — that we might be asking too many questions, demanding too many answers, falling on our faces too publicly. I was around Ramona’s age when I became extremely shy. I doubt I ever came across as too much to anyone. How could I? I was determinedly agreeable, dutiful, observant, compliant, reliable. And do you know how much effort that took? How much physical, mental and emotional labor to stay so small and so silent? I think Beezus would. In fact, I was so good and so silent for so long that I forgot until just now — until that news alert tonight, in fact — that staying that still and that silent took so much work.

And that’s because on the inside, I was a stomping in puddles, skinning my knees from rollerblading down that hill, loudly proclaiming my beliefs — of which I had many, even then, especially then. I was too much in the best ways.

Outside this space, I sometimes forget that not everyone understands what I mean when I talk about adventures. Not everyone understands what I mean when I say that wonder (the act of marveling) is one of my core values. And that’s more than OK because different things mean different things to different people. But I began these conversations because I suspected there were women out there (all over) who didn’t necessarily equate “adventure” with cliff diving, for example.

There’s something about smart women (and men) who show up but are usually pictured just off center frame that remind me of big things happening under the surface. The big skills and big feelings and big ambitions. And, yes, the big insecurities and big regrets too. But it’s why the world doesn’t seem too big (or too anything) for them or for me. It’s why these conversations celebrate outward success but also visceral, sensory memories.

It’s why I am so driven to share the interior lives of women who might have been a little too precocious, a little too messy, a little too all over the place (even if only in their hearts). And it’s also why I’m not interested in simply speaking to women who reflect back my reality and my upbringing (Ramona or Anne or Jo aren’t everyone’s touchstone characters, nor should they be).

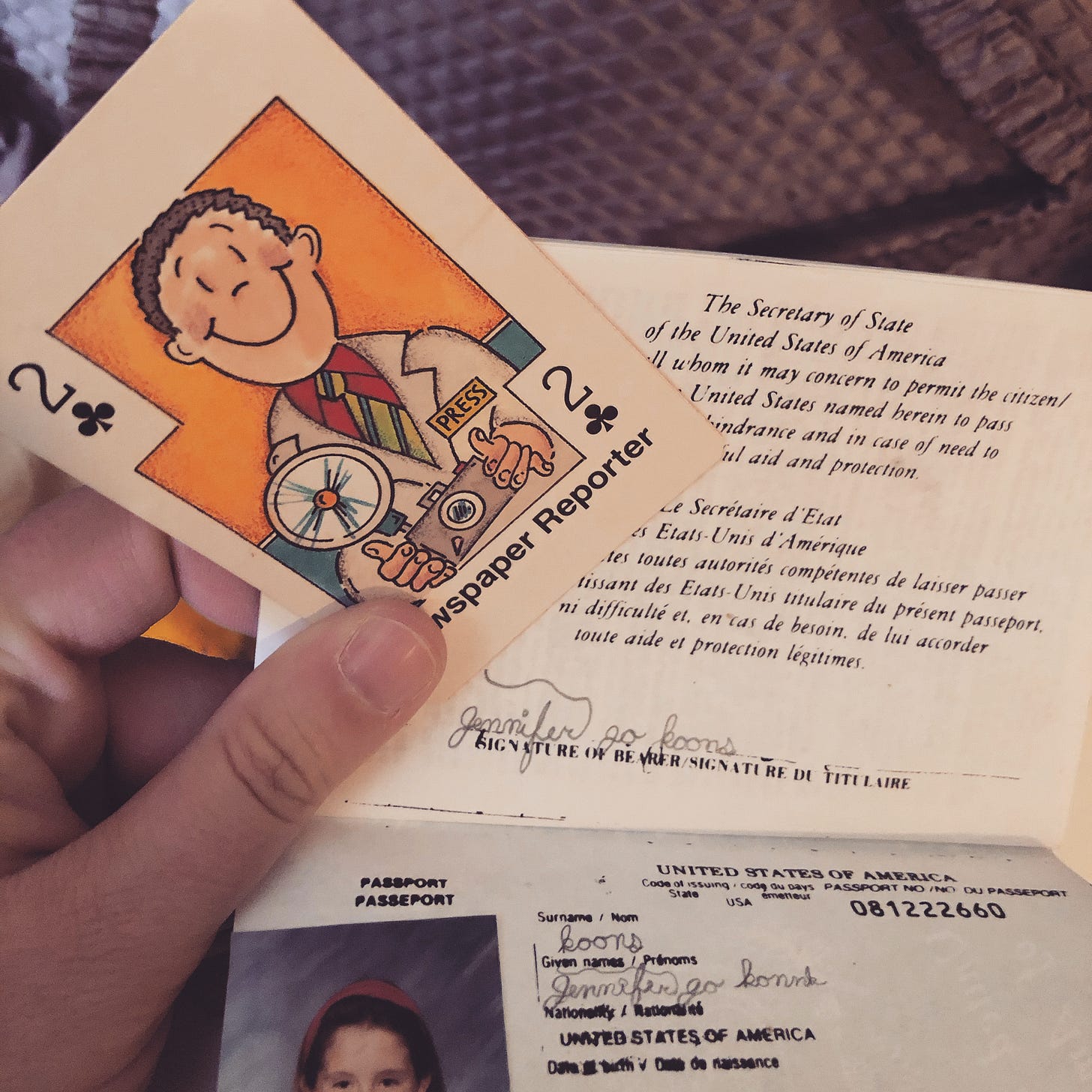

I’d love to hear about your “red rain boots” (what you craved as a kid and are craving tonight). I’d love to hear about who reflected back the values you have come to hold dear. And I’d love for you to share in the comments (or with me directly at jennifer.koons@protonmail.com) knowing that you’re reflecting that knowing — that wonder (and so much more) back to everyone who reads this.

Below, please enjoy a brief sampling of when and how a few of those with whom I have already had the privilege of speaking first knew that they would be at home in the world. For the complete interviews and access to the full archives, click on this button:

M.J. Crawford:

I have been lucky to be able to travel to many different places around the world. Outside of my own home in the United States, I really enjoy living and traveling throughout the post-Soviet countries. I have either lived in or traveled solo throughout 12 of the 15 post-Soviet countries, including a few of the frozen conflict territories. There is a lot about this region that honestly reminds me of my home state of Michigan.

Flint and Detroit are both industrial cities and I have found a lot of similar machinery and styles of architecture while traveling throughout the old industrial cities of the former Soviet Union.

There is a lot of soul and history to the region that echoes where I come from, but not a lot of Black Americans tend to travel there, which is a shame. The people I met along the way were very kind.

Taylor Cofield:

I knew that I would be and perhaps more importantly, could be at home in the world in 2016 when my time living in Madaba, Jordan, came to an end and I tried to do just about anything to stay; a ending that was a firm contrast from the start of my very first venture outside of the United States.

I arrived in Jordan after being awarded the Critical Language Scholarship through the U.S. Department of State in order to advance my Arabic and immerse myself into Jordanian society, but I gained so much more.

However, my first two weeks in the country were overwhelming, to say the least. Suddenly, I recognized that nothing was mine any longer—not the culture I was navigating, not the family I was living with nor the home I was living in, and not the language I was attempting to communicate in. That realization required me to make a home in my newfound city with my new family, and participate in a new culture and society; and I did just that.

By the end of my stay, it was hard to believe that I hadn’t always lived in Madaba because it started to feel more like my home than my real home, in large part because I think I began to acknowledge that I was placed in Jordan for a reason and the friends and family I made would serve a larger purpose and that purpose is what I refer to as “Maktub”or the Arabic word literally translated as it is written.

For me, “Maktub” is the only word that can express this concept of destiny that I felt as I found a sense of home in Jordan; the only way to illustrate my journey to becoming a U.S. diplomat that began with a seemingly arbitrary decision to study Arabic and the pure happenstance I would end up in Madaba, Jordan—as if it had already been written. From then on, I knew I would be home anywhere.

Zehra Bell:

I felt at home in the world from the very beginning. My mother is from Mombasa, Kenya and my father from Zanzibar, Tanzania. I distinctly remember being weird, being an outsider in my elementary school. My food smelled funny and my culture (as the only Muslim kid) made me feel at times so alone.

I became convinced early that I would belong more in the world and I feel like I was proved right!

Melinda Crowley:

It’s not just one episodic event for me. It’s a continuum. When I retrace the years, my family really planted the seeds that I would credit for paving the path toward my career as a diplomat.

It began with the National Geographic magazines that were a fixture in my grandparents’ home. You could explore the world, learn about new cultures and how others organized their lives. My mom also introduced me to the culture of penpals. Again, we were young [me and my penpals] and we were seeing things that were totally different than how we each lived. Growing up, what seemed like ordinary moments, along the way, when you thread them together, they really now add up to extraordinary experiences and opportunities that taught me not to fear what is different than me and fostered a can-do attitude where my family unleashed in me the potential to be comfortable in the world and to venture out in the world with confidence. Those are all my original passports, if you will.

But if I had to pick one: I was on an independent study program through Syracuse University in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa. And it was led by an African woman, a professor.

I wanted to be introduced to Africa for the first time by an African.

As an African-American, I romanticized the stories and the notions [about Africa]. What I had experienced was completely different. So I was part of this special team of students that she took. And we went to this village in Zimbabwe, and the local women started dancing. Well, I took dance all my life, and I knew the dance. And I joined in. I couldn’t believe it. With African dance in the States, you always think, “is this really African dance or is this just a way to label it?” And so in that moment, I realized, “OK, I’m home.”

Know a Woman in Foreign Policy Who Should Join our Conversation?

Share in the comments below or email me at jennifer.koons@protonmail.com.